Liang Qichao and The Chinese Way of the Warrior

Introduction

In the latest episode of my YouTube series, The Secret History of Xingyi Quan (Episode 8), I explored the sweeping reforms and cultural changes that reshaped Chinese martial arts during the Republican era. This was a period of enormous transition in China, when centuries-old traditions collided with new ideas about modernization, nationalism, and physical culture. Martial arts were no longer just the domain of private masters or bodyguards — they began to be recast as part of a national project to strengthen the people and preserve cultural identity.

During the episode, I mentioned the late Qing dynasty reformer Liang Qichao, a towering intellectual whose writings deeply influenced how Chinese society thought about strength, vitality, and martial spirit. One of his most significant works in this regard was his essay The Chinese Way of the Warrior, a piece he wrote during his exile in Japan following the failed Hundred Days Reform. It was in Japan that Liang was exposed to the rising ideology of Bushidō and the martial spirit that underpinned the Japanese national mentality at the time. Struck by the contrast between Japan’s martial vigor and China’s perceived complacency, Liang argued that China needed to rediscover and cultivate its own warrior spirit if it was to survive in a changing world.

Liang Qichao 梁啓超 (Born February 23, 1873 - Died January 19, 1929)

Liang Qichao: A Reformer in Exile

Liang Qichao (1873–1929) was born in Xinhui, Guangdong, at a time when China faced mounting crises from foreign invasions, unequal treaties, and internal decline. A precocious student, Liang gained early fame as a writer and quickly rose to prominence as a disciple of Kang Youwei, the reformist scholar who spearheaded the ill-fated Hundred Days Reform of 1898. The reform movement sought to modernize China’s institutions, education, and military along Western and Japanese lines, but it was crushed by conservative factions at the Qing court.

When the reform failed, Liang fled to Japan to avoid persecution (and certain execution). This period of exile would prove transformative for his thinking. In Japan, he witnessed firsthand a society that had undergone rapid modernization during the Meiji Restoration. More importantly, he encountered the emerging concept of Bushidō — the “way of the warrior” — which was not only a code of conduct for samurai but was increasingly promoted as the moral and spiritual foundation of Japan’s modern nationhood.

For Liang, who lamented the decline of China’s martial vigor and the dominance of civil culture over military preparedness, Bushidō represented a stark contrast to China’s condition. In his writings, he began to argue that China must rekindle its own martial spirit — not simply in terms of armies and weapons, but as a cultural ethos that fostered courage, sacrifice, discipline, and national unity. This conviction found its clearest expression in his essay often translated as The Chinese Way of the Warrior.

The Chinese Way of the Warrior

In 1904, Liang Qichao published The Chinese Way of the Warrior (《中国之武士道》) under his pen name The Master of the Ice-Drinker’s Studio. At its core, this work argued a simple but powerful idea: Japan was becoming strong because it embraced a martial ethos, while China was declining because it had lost its own. Liang believed that only by rekindling a martial spirit could China once again become rich, powerful, and independent.

Deeply inspired by the Japanese model, Liang held that Bushidō’s loyalty, courage, and self-sacrifice had fueled Japan’s rise. He contrasted this with what he saw as China’s complacency and overemphasis on civil culture, which had led to weakness in the face of foreign aggression. Yet Liang insisted that martial spirit was not alien to China. In his preface he declared:

“The Chinese people’s martial character was our original nature. Its disappearance was only a secondary nature, created by circumstances. If circumstances could strip us of it, then human effort can restore it.”

His book was both a historical study and a call to action. Liang combed through China’s past, highlighting heroic figures who embodied martial virtue, and presented them as models for the modern age. He sought to create a program of “spiritual education” that could restore courage, loyalty, and readiness to sacrifice for the greater good.

However, unlike Japan, China lacked a hereditary warrior class that codified a national ethos like Bushidō. Critics such as Yang Du observed that deep-seated cultural traditions — from Daoist longevity practices to Yangist philosophy emphasizing self-preservation — ran counter to Bushidō’s glorification of sacrifice. Because of this, Liang’s project had limited impact. While it inspired ideas of “strengthening the nation through physical education” and helped pave the way for groups like the Jingwu Athletic Association, it never succeeded in transforming China’s national character in the way he envisioned.

Martial Arts Reform in the Republican Era

Liang’s ideas nevertheless resonated in the broader reform of martial culture during the Republican era. The Jingwu Athletic Association, founded in Shanghai in 1910, openly promoted martial arts as tools for public health, discipline, and national strength. Unlike traditional factions bound by secrecy and lineage, Jingwu emphasized standardized curricula and accessibility.

This spirit carried forward with the founding of the Central Guoshu Institute in Nanjing in 1928 under the Nationalist government. The institute was tasked with unifying martial arts into a national system that could improve the health of citizens and foster patriotism. National competitions, teacher appointments, and training programs were all designed to elevate martial arts to the level of state-sponsored cultural education.

Like Liang’s essay, these efforts were not without contradictions. Martial arts had to be reshaped into modern physical culture while still carrying their traditional combat essence. Yet, they succeeded in one crucial respect: they cemented the idea that martial arts were central not only to individual practice, but to national identity and resilience.

Xingyi Quan and the Warrior Spirit

If Liang Qichao sought a model of Chinese martial spirit, he could have found it in Xingyi Quan. The classic teachings of Xingyi are heavily laden with the ethos of the warrior: directness, courage, sacrifice, and indomitable will. Throughout history, Xingyi Quan produced some of the most formidable martial artists of China’s past — individuals known not just for their fighting ability, but also for their iron discipline and unyielding character.

During the Republican era, many of the greatest martial educators and organizers also came from Xingyi backgrounds, carrying forward the warrior ethos into both teaching halls and national institutions. Their contributions ensured that the martial values Liang longed to revive were not lost, but were actively shaping the modern development of Chinese martial culture.

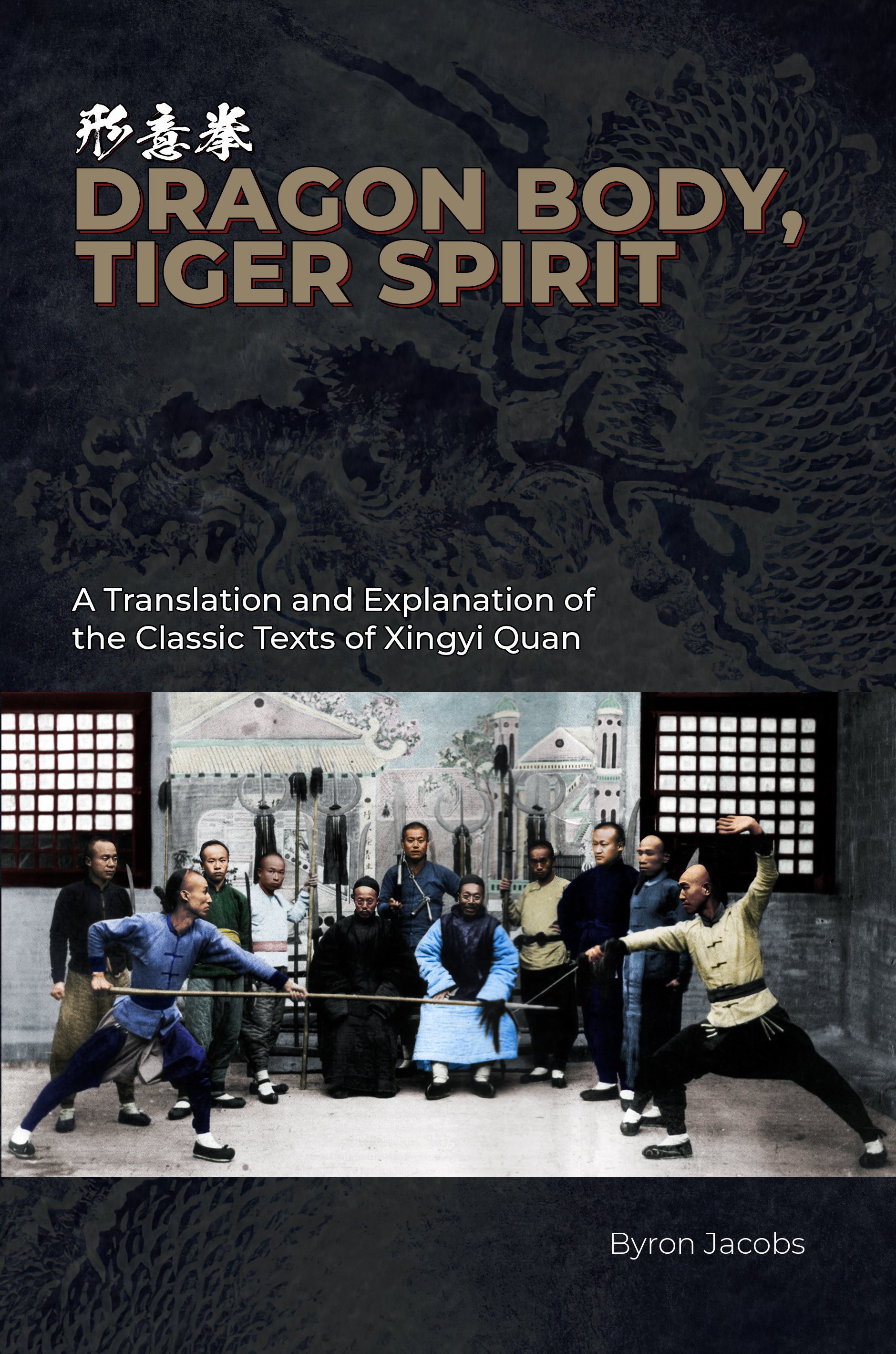

Further Reading: Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit

For those interested in exploring this connection more deeply, my book Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit – A Translation and Explanation of the Classic Texts of Xingyi Quan presents these warrior teachings in detail. The classic texts of Xingyi Quan are not simply technical manuals; they are philosophical blueprints, expressing the mindset, spirit, and values of China’s warrior tradition.

This book offers complete translations of the foundational writings of Xingyi, along with explanations drawn from years of training and research. It highlights exactly why Xingyi Quan produced some of China’s most notable fighters and educators — men who embodied the warrior spirit that Liang Qichao believed was vital to national survival.

You can order Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit directly from mushinmartialculture.com or from Amazon.

Conclusion

Liang Qichao’s Chinese Way of the Warrior was a bold attempt to confront the weakness of late Qing China and to call for a revival of martial ethos. While his vision was never fully realized, it framed an important conversation about the role of martial spirit in cultural and national renewal. The reforms of the Republican era, and the enduring warrior tradition of systems like Xingyi Quan, show that his concerns were not misplaced.

For modern practitioners, Liang’s call still resonates. The martial arts we practice are not simply systems of combat; they are carriers of values — perseverance, courage, discipline, and resilience — that remain as vital today as they were in Liang’s time.

If you’d like to explore these themes in more detail, I invite you to watch Episode 8 of The Secret History of Xingyi Quan on my YouTube channel, where I dive into Liang Qichao, martial reform, and the cultural forces that shaped Chinese martial arts in the Republican era.