Old China Through a Western Lens - The North China Herald (1) - “Chinese Boxing” 1872

The North China Herald (1850 - 1941)

The North-China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette was published in Shanghai as the weekly edition of the North-China Daily News from 1850 until 1941. It was a foreign owned, English language publication distributed to the then ex-pat community in China and today serves as a prime printed source for the history of the foreign presence in China from around 1850 to 1941. No other English newspaper existed in China over such an extended period, and covers it in such incredible depth and variety. Today, it is an incredible window into old China. I have been searching through archives of this publication and will be pulling out interesting articles that feature martial arts, culture and other points of interest and sharing them here.

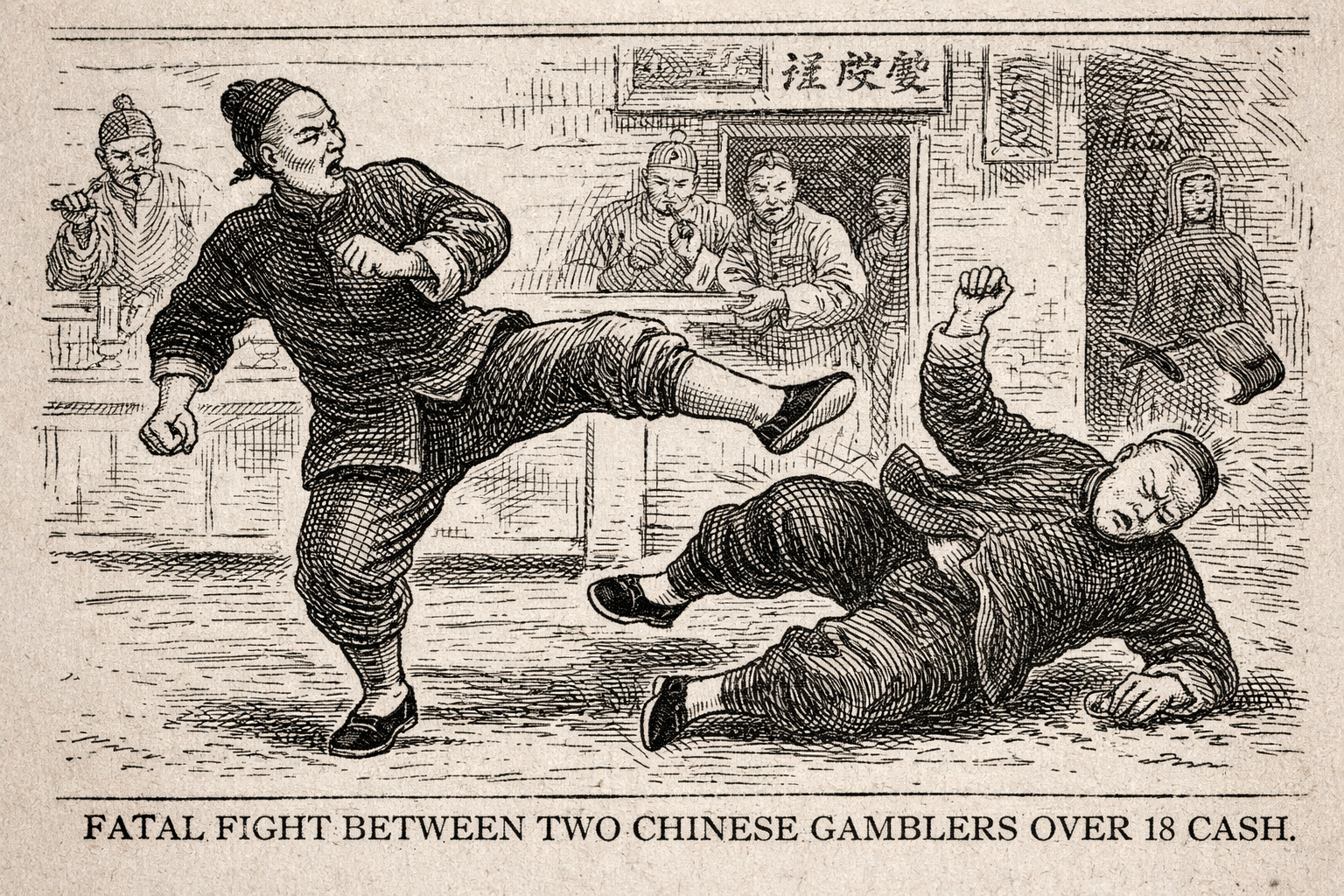

This first article I am presenting was published in Shanghai on July 13th, 1872 and is titled “Chinese Boxing” featuring an account of a match between two Chinese gamblers at a teahouse that resulted in a fatality. The article highlights that Chinese combat included the regular use of the legs and how this was something that caused great injury or worse.

There are glimpses of the then total ignorance westerners had regarding Chinese martial arts, as well as other negative character expressions from the author identifiable in the article, but a valuable piece of history nontheless.

It is transcribed below for your reading.

Re-created image (not from orignal publication)

CHINESE BOXING

If there is one particular rather than another in which we might least expect to find John Chinaman resemble John Bull, it is in the practice of boxing. The meek celestial does get roused occasionally, but he usually declines a hand to hand encounter, unless impelled by the courage of despair. He is generally credited with a keen appreciation of the advantages of running away, as compared with the treat of standing up to be knocked down, and is slow to claim the high privilege the ancients thought worthy to be allowed only to freemen, of being beaten to the consistency of a jelly. How the race must rise in the estimation of foreigners, therefore, when we mention that the noble art of self-defence and legitimate aggressiveness flourished in China centuries probably before the “Fancy” ever formed a ring in that Britain which has come to be regarded as the home of boxing. Of course, like everything else in China, the science has rather deteriorated than improved; its practice is rough; its laws unsystematized; its professors are not patronised by royalty nor petted by a sporting public; the institution is a vagabond one, but an institution nevertheless.

Professors of the art, called “fist teachers,” offer their services to initiate their countrymen in the use of their “maulies,” and, in addition, in throwing out their feet in a dexterous manner. As hitting below the belt is an outrage on fair play, so with the Chinese certain reservations are made as to the portions of the body that may be kicked or cuffed. Boxing clubs are kept up in country villages, where pugilists meet and contest the honours of the ring. Unfortunately, popular literature does not take cognisance of the little “mills” in which the Chinese boxer may “come up smiling, after round the twenty-fifth,” nor are the referees, if there be any, correspondents of sporting papers, so that we are unable to tell whether the language is rich in such synonyms as “nob,” and “conk,” and “peepers,” and “potato trap.” But if the boxers appreciate, as much as their foreign brethren, the advantages over an ignorant and admiring mob which the assumption of a peculiar knowingness gives, we may well suppose that, as they smoke their pipe and sip their tea, they talk over the prowess of the Soochow Slasher or the Chefoo Chicken in a terse and mystic phraseology, embellished with rude adjectives and eked out by expressive winks.

We are not unused to hearing of fatal encounters in the Western ring, where the brutal sport is hedged about with restrictions intended to guard against its most serious eventuality, but in China homicide in such affairs is made more frequent by the admission of kicking. A case of the sort has just occurred at Tachang, a village about eight miles due north from the Stone Bridge over the Soochow Creek. In a teashop where gamblers and boxers were wont to meet, a dispute arose between two men about 18 cash, and it was arranged to settle it by fighting. After a few rounds, one man succeeded in knocking over the other, with a violent kick in the side. The man sprang to his feet, exclaiming “Ah! that was well done,” and as he advanced to meet his antagonist again, suddenly fell back, dead. Consternation fell on those concerned in the matter, and every effort was made to evade a judicial enquiry. The relatives of the deceased, however, came forward to make the usual capital out of their misfortune. They seized the homicide, put him in chains, and bound him for two days and nights to the body of the dead man, which had been removed to the upper part of the teahouse. An arrangement for a pecuniary salve to their lacerated feelings was made, by which the people in the neighbourhood paid $150, the teahouse keeper $100, and the dealer of the fatal blow $50. But gambling and fighting had drained the resources of the latter, he was an impoverished rowdy, without a respectable connection in the world, except the betrothal tie, by which the fate of a young lady was linked with his, before either had a will to consult or the wayward tendency of his character had appeared. Glad of an opportunity to break off the engagement, the young lady’s friends came forward and offered to pay the sum if he would surrender all claim to his fiancée. The offer being accepted, the whole affair was settled; the sum of a Chinese boxing match being thus one combatant killed, a teahouse keeper ruined, a neighbourhood heavily fined, and a marriage engagement broken off. Probably such incidents occur very often, but if the parties can settle it among themselves, the magistrates, for their own sakes, are only too glad to have the matter hushed up.

Original article (1)

Original article (2)