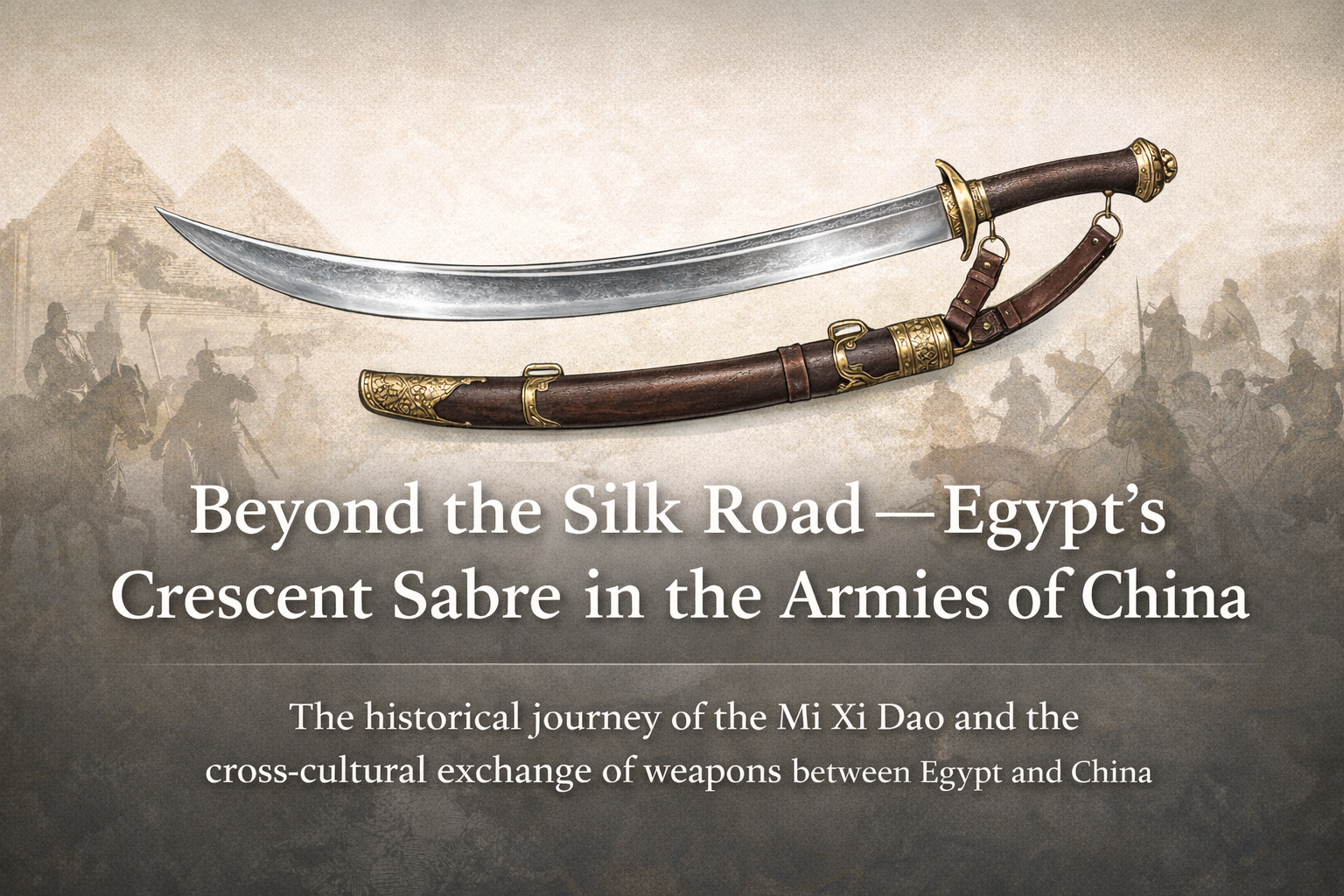

Beyond the Silk Road — Egypt’s Crescent Sabre in the Armies of China

Professor Ma Mingda, the Mi Xi Sabre, and a Window into Cross-Cultural Martial Exchange

The following research article was written by Professor Ma Mingda, a renowned historian, distinguished scholar of traditional martial culture, and leading inheritor of the Ma family martial arts lineage. Professor Ma has long been recognized as one of the most respected voices in martial arts studies in China, combining rigorous academic methodology with a lifetime of personal training and family transmission.

In our ongoing interview series on the Mu Shin Martial Culture YouTube channel, Professor Ma speaks extensively about the evolution of martial systems, the transmission of technique, and the often-overlooked role of cross-cultural contact in shaping Chinese martial arts over time. In one episode he specifically references the Mi Xi Sabre (米息刀), a weapon of Middle Eastern origin whose presence in Yuan and Ming China reveals a fascinating history of exchange, adaptation, and absorption between martial cultures.

I have been fortunate to maintain a long relationship with Professor Ma and his son, Professor Ma Lianzhen, who continues both the family’s martial heritage and its academic research tradition. It was through Ma Lianzhen’s generosity that I was granted access to the original text which I translated below. This work offers valuable perspective on the Mi Xi Sabre, its origin, transmission into China, and the broader network of cultural exchange that influenced Chinese weaponry and martial technique.

What follows is my full English translation of Professor Ma Mingda’s article, Research on the “Mixi Dao”, originally published in Studies in Maritime Exchange History (Issue One, 2000; revised 2006). Below is the translation I have compiled of that article.

Research on the Mi Xi Sabre

In the Yuan dynasty, there existed the “Mixi Sabre” (米息刀), recorded in Volume 4 of Yusi Ji by the late Yuan poet Zhang Xian, in the poem “Song of the Western Regions Sabre Presented by Xuanyuanjie of Beiting”, which reads:

Tang people boasted of treasured Arab sabres,

Today the finest blade is called Mixi.

Ten years of earth-washing gives birth to pine-grain patterns,

Forged by the king of warriors beneath a lunar eclipse. (1)

The line “Tang people boasted of treasured Arab sabres” refers to Du Fu’s poem “Song of the Arab Sabre for Marshal Zhao Gong of Jingnan”. (2)

“Today the finest blade is called Mixi” indicates that in the Yuan dynasty, the Mixi Sabre was regarded as the most outstanding weapon.

Its manufacture appears to have been elaborate. Firstly, the blade bore pine-grain patterns, formed only after a special treatment called “ten-year earth washing”, the exact method of which they used remains unclear today. Secondly, like ancient Chinese swordsmiths forging only on selected days, the “warrior-king” forged sabres specifically during lunar eclipses, suggesting the production region placed great importance on lunar cycles.

By contrasting the Arab sabre (大食刀) with the Mixi, the poet implies more than wordplay, hinting at cultural or technological connections.

Professor Ma Mingda

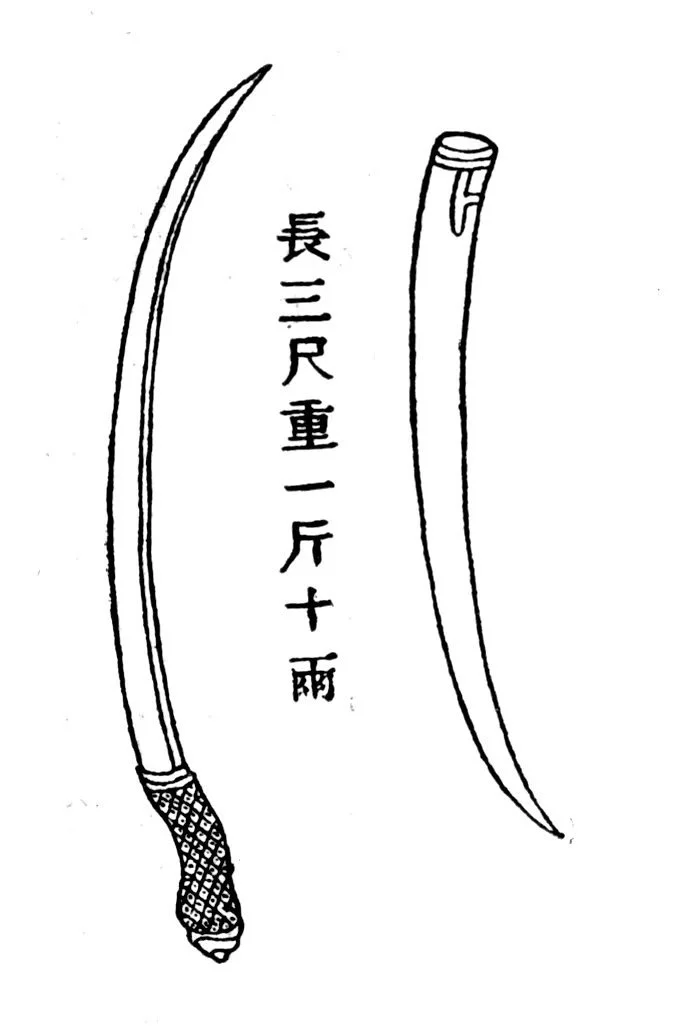

During the Ming dynasty, the military also possessed Mixi Sabres, as seen in Qing-period Supplement to the Comprehensive Study of Literature Vol. 134, “Weapons”:

In the first month of the 13th year of Hongwu,’s reign (1383) the Bureau of Military Weapons was established to manage ordnance. The “Collected Statutes” records… Among the sabre types were: Mo Suo Dao, Pei Dao, Gun Dao, Wo (Japanese) Gun Dao, Mi Xi Dao, Huang Lian Dao, Kai Nao Da Dao, Da Yang Mo Suo Dao, Ma Dao — each with different fittings. (3)

In Ming Hui Dian (Ming Collected Statutes) Vol. 123 under equipment issued to military officers appears the entry:

In Ming Hui Dian Vol. 123 under the Ministry of War, section eighteen “Five Armies Command,” the list of equipment issued to officers and soldiers, which states:

“…including armor, spears, sabres, bows and arrows” it contains the entry “two Mi Xi sabres with full accoutrement (scabbard and leather suspension belt).”

This demonstrates the sabre’s official military use.

The weapon also appears written as “Mí Xī Sabre (糜西刀)” in He Liangchen’s Zhen Ji (4).

Therefore, the various characters used for Mi Xi Dao/Sabre “米息刀”、“米昔刀”、“糜西刀” should represent the same weapon. According to Yuan transliteration, it likely abbreviates Misi'er / Mixi'er, the Yuan-Chinese name for Egypt, first appearing in Liu Yu’s Record of the Western Envoy as Miqi’er or Mixi’er (5).

Thus, Yuan- and Ming-era Mixi Sabres were either direct imports from Egypt or Chinese reproductions of Egyptian blades. The arrival of Egyptian sabres into China’s military, a topic that has rarely been noticed or discussed in the past by scholars, is historically significant in Sino-foreign cultural exchange, Chinese weapons history, and martial arts history as a whole.

In the early Yuan, Egypt under the Mamluk Sultanate was the strongest power in North Africa. In September 1260, Mongol troops under Hulagu of the Ilkhanate clashed with Egypt at Ayn Jalut, where the Mongols were defeated, halting expansion into North Africa. Egypt thereafter maintained relations with the Golden Horde to check Ilkhanate influence (6).

Mamluk Sultanate

Records of direct Yuan-Egypt contact are scarce, but Mi Xi Sabres did enter China as tribute late in the dynasty. Yuan History Vol. 43 records:

In the ninth month of the 13th year of Zhi Zheng’s reign the land of Zha Ni Ze made offerings from Sahara, Chaqier of Mixi’er sabres, bows, chain armour, and white western horses; 20,000 ingots in paper currency were bestowed in return. (7)

While the location of Zha Ni Ze is unclear, Sahara, Chaqier, Mixi’er are African regions, and the inclusion of Mixi’er Sabres as tribute shows they were high-grade and sought after swords and a specialty of that region.

During the Yuan Dynasty, due to the unprecedented development of Sino-Western trade, sabres made in Islamic countries of Central and West Asia were introduced to China through various channels. These sabres were usually called "Hui Hui sabres," (Hui Hui refers to Han Chinese Muslims) and the Mi Xi sabre was likely one type of Hui Hui Sabre. However, the Mi Xi sabre was a military weapon, specifically a cavalry sabre, so it had a specific name that indicated its origin, suggesting it was a product of Egypt during the Mamluk Sultanate period.

Concerning the “Huihui Sabre” of the Yuan dynasty, we can list at least two examples.

First, Zhou Mi’s Yunyan Guoyan Lu Volume Four records:

“Liu Hanqing possessed a small Huihui sabre. On the spine there was all gold-inlaid Huihui script, and within, gold inlay formed a human-face beast pattern. Extremely exquisite. It was said to be what the king of the Huihui country wore on his side.” (8)

According to this, Liu Hanqing is the same as Hudu Temur. Yuan History Volume 122 contains his biography. He was the son of Temaichi of the Helu clan. Temaichi was a military official, having achieved repeated merit. Hudu Tiemulu inherited his post by virtue of his father’s rank, followed Bayan in pacifying the Song, and afterward served in official posts in southern China. The biography records that he “liked reading books, associated with scholars and officials, and had the stylized name of Han Qing. … His mother’s surname was Liu, therefore people also called him Liu Hanqing.” (9)

Zhou Mi was one of his friends, as is reflected many times in Zhou Mi’s Guixin Miscellaneous Notes. For example, in the entry “Western Region Jade Mountain,” it says: “Liu Hanqing once followed government troops to the Small Huihui Country, several tens of thousands of miles from Yan. After every rainfall, the mud of the mountains is washed clean; for several hundreds of miles the jade mountains shine upon one another, with blue crystals rising several feet high. Could these be what are called langgan (lapis lazuli)?” (10)

What “Small Huihui Country” refers to is not known; it is suspected to be Khwarazm , termed “small” in order to distinguish it from the Abbasid Caliphate of the Arabs. These two pieces of information from Zhou Mi seem to indicate that Liu Hanqing’s “Huihui Sabre” came from Khwarazm, originally belonging to the Sultan of Khwarazm as his personal saber.

Khwarazmian Empire 1215

The second reference for Huihui sabres is in Yuan Huang Jie’s Bianshan Xiaoyin Yinlu Volume 2 there is a poem titled “Marshal Yuquan Shows Me His Belted Sword, Made by the Huihui, Like a Goose Feather, with Snow-Colored Grain Patterns Worth Viewing.” (11) The content of the poem quotes classics and historical references, but is unrelated to the topic, so it is not included here. Judging from the title alone, the sabre owned by Marshal Yuquan was also a blade made by the Huihui, but its form was like a “goose feather,” which shows that it was not a Mixi Sabre, because the most distinctive feature of the Mixi Sabre is that it is shaped like a crescent.

In Ming-dynasty texts, materials concerning Mixier - Egypt (also written Mixier, Mishi-le, and so on) are very few, and cannot truly reflect the relationship between the Ming dynasty and Egypt. Ma Huan, in the “Travel Poems” at the beginning of Yingya Shenglan, once mentioned “Dayuan and Mi Xi have active trade,” which is one of the earlier recorded examples in Ming sources. As an attendant of Zheng He, Ma Huan may have learned about Mixier while in Tianfang (Kaaba-Mecca), knowing that Mixier (Egypt) had frequent commercial exchange with Mecca and other places. (12)

In Ming Veritable Records regarding Mixier (Egypt), there are only four entries of missions offering tribute during the ninth and tenth months of the sixth year of Zhengtong Emperor Yingzong reign, and no other records. (13)

History of Ming · Western Regions IV · Mixier states:

“During the Yongle reign, envoys were sent to offer tribute. After the banquet, they were ordered to receive wine and meals every five days, and feasts were arranged at every place they passed.”

It also states that in the sixth year of Zhengtong, the King of Mixier, Sultan Ashirafu again came to offer tribute, and the Ming court officially established the ‘gift regulations,’ but ‘afterwards they did not come again.’ (14)

These scattered materials show that official exchanges between the Ming and Egypt mainly occurred before the reign of Emperor Yingzong, and after Yingzong’s passing there was no further contact. Other Ming books such as Haiguo Guangji, Huangming Xiangxu Lu, Huangming Shifa Lu, and later Zuiwei Lu, all record another name for Egypt, “Wu Si Li” and the content recorded is more than that of Veritable Records. (15) However, the content in these works is mostly identical, and is basically copied from Zhao Rushi’s Song-dynasty Zhufan Zhi, lacking much historical value.

As previously mentioned, the History of Ming (Western Regions section) records that during the Yongle period envoys from Mixier (Egypt) came to the Ming court. As to whether the Ming dynasty also sent envoys to Mixier (Egypt), there is no concrete account in Ming historical records. However, History of Ming · Western Regions has one description stating:

“During the Hongwu period, Taizu wished to open relations with the Western Regions, repeatedly dispatching envoys to instruct and summon, but rulers of the far western lands had not yet come. In the ninth month of the twentieth year, Timur (Tamerlane) for the first time sent the Huihui Manla Hafeisi and others to court, offering fifteen horses and two camels. An imperial banquet was ordered for the envoys, and eighteen ingots of white silver were bestowed. From then on, tribute of horses and camels was given every year. In the twenty-fifth year tribute additionally included six pieces of velvet, nine bolts of blue gauze, two pieces each of red and green sahara cloth, as well as fine-steel sabres, swords, armor, and various items.” (16)

Whether the “wishing to open relations with the Western Regions and repeatedly sending envoys” included Mixier (Egypt) is unclear. But firstly, among the tribute goods from the Western Regions were “fine-steel sabres, swords, armor and such items”; secondly, in the surviving Yongle Dadian we find two passages related to this, proving that in early Ming envoys indeed reached faraway places such as Mixier (Egypt).

Yongle Dadian Volume 3526, Jiuzhen · Gate:

“Yuanshuiguan Gate — In the land of Misi’er (Egypt), there is a clear river called Nile. Above the source of the river there stands Yuanshuiguan Gate, shining with radiance. On all four sides are gates suspended in the air. At the beginning of spring every year, the gates open by themselves, and water flows out from the eastern gate, continuing for forty days until the gates close. After closing, water always trickles out beneath the threshold.” (17)

Again, Yongle Dadian Volume 22182· Wheat:

“Mixi’er (Egypt) Wheat — The present dynasty dispatched envoys to the land of Misi’er (Egypt), saying: in that country there is a clear-water river, along whose banks ancient cultivation once existed, but now only mixed fruit trees remain. The remnant wheat seed there is as large as soybeans, and grows spontaneously.” (18)

Both of these materials refer to the situation in Mixi’er (Egypt). The first seems to describe rapids or some form of irrigation structure in the upper Nile. The second describes a superior wheat variety of the Nile River region. When Dadian quoted these materials, the original sources were not indicated. The phrase “the present dynasty dispatched envoys to Mixi’er” with “present dynasty” written in elevated script clearly refers to the Ming dynasty, and the time was very likely during Hongwu. These two passages should originate from a single work, possibly a report of officials sent to Mixier (Egypt), or perhaps a private work of an official within the mission. Because Dadian did not indicate the source as usual, it is more likely that the material came from a government envoy report.

In the early Ming, the Mixi Sabre may have entered China through “tribute” as well as civil trade and other channels, and there may also have been remnants from the Yuan Dynasty. In any case, because of its excellent quality and its effectiveness in battlefield cutting and killing, during the Hongwu era the state weapon-making institution specifically produced it to equip the military. This very likely continued the legacy of the Yuan system, and also correlates with the large number of Central Asian Muslims who submitted and later served in the military during early Ming Dynasty. Furthermore, Arab lands were famous for sword-making; as early as the Tang dynasty, the Arab Sabre (Dashi Dao) had already entered China. During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, Arab “fine-steel (bin tie – possibly what is known today as Damascus steel)” was imported into China in large amounts, mainly for weapon production, and the Mixi Sabre was very likely made from such fine steel. (19)

Ming weapons, especially short weapons such as sabres and straight swords, were largely imported from foreign areas, and also replications were widely produced based on imported foreign weapons. The primary focus of import and imitation was on swords from Japan, which became a major characteristic of Ming weaponry. Ancient weapon expert Zhou Wei pointed this out clearly a long time ago. (20) This may have been a remnant of influence from of the Yuan dynasty, but also occurred due to the gradual decline of the official metallurgy and forging capabilities of the Ming dynasty and as such its sabre quality could not match that of foreign lands, thus making the reliance on imports and replication necessary. Among the various weapons produced by the Ming Armament Bureau previously mentioned, the Mo Suo Dao Sabre, Large Mosuo Dao Sabre, Japanese Gun Dao Sabre, and Mixi Sabre should all have been replications. And regarding the replication of Mixi Sabres and their allocation within the army, we may also find evidence.

During the Jingtao period of reign by Emperor Yingzong of the Ming Dynasty, the Yao people of Xunzhou (present-day Guiping, Guangxi) launched a rebellion against the Ming. The rebels held their ground on the dangerous mountain terrain and local troops could do nothing. In Chenghua Year One (1465), the court decided to send forces; military affairs were effectively led by the famed general Han Yong, who held the post of Left Vice Censor-in-Chief. (21) In response to the Yao setting stockades up on mountain peaks, using rolling logs, dropping stones, using darts, spears and poison crossbows to repel government troops, Han Yong proposed mobilizing “Daguan Troops” from Nanjing, which included Muslims of various Western Region origins who had submitted to the Ming. History of Ming · Biography of Han Yong does not specifically record this, only saying “Yong rushed to Nanjing and assembled various generals to discuss strategy.” (22) Historical Events of the Ming · Pacifying Teng Gorge Rebels states:

“Yong also requested the transfer and mobilization of over one thousand Daguan troops, assigning a deputy general to command them. The Yao, moving in and out of forests and mountains, relied on short weapons such as javelins and shields and sabres, which were ineffective against mounted archers. Therefore, the Daguan troops prevailed wherever they went and the rebels feared them.” (23)

Besides having superior horsemanship and archery skills, Han Yong specifically equipped them with a type of curved steel sabre, which should be the Mi Xi Sabre. This is known from Han Yong’s poetry. In Xiangmin Ji Volume 8, there are four seven-character quatrains titled “News from Guangdong of the Rebel Dispersal, Receiving Zhao’s Poem of Grace Concerning Bow and Hooked Sabre, Written in Harmony and Gratitude,” the fourth of which reads:

Newly outfitted steel sabres curved like the moon,

Well suited for scaling lofty mountains and steep ridges.

Grateful for your gift as I march south to pacify,

Soon together we shall settle the northern barbarians. (24)

Yao Ethnic Group

The so-called “newly outfitted steel sabre” must refer to the curved steel sabre specially made by the Ming government for the Daguan Troops, or to the Mixi Sabre produced by the Armory Bureau. Han’s poem says the special advantage of this sabre is “well suited for scaling lofty mountains and steep ridges,” clearly indicating that it was specifically equipped for the Daguan troops responsible for advancing through narrow mountain paths.

Additionally, the “Yao Dao” (waist sabre) was the main short weapon of the Ming dynasty, issued widely within the army, but its form was extremely diverse, with no single standard. Ming Waist Sabres differed for cavalry and infantry, and infantry versions varied in length. We note that some Ming Waist Sabres clearly show features of the Mixi Sabre — that is, the blade had an obvious “crescent curve.” This style of sabre appears in Qi Jiguang’s Ji Xiao Xin Shu (New Treatise on Military Efficiency), as well as in Mao Yuanyi’s Wubei Zhi (Records of Armaments and Military Provisions – Bubishi)

The introduction of weapons implies the introduction of martial skills, the imitation of weapons implies imitation of their methods of use and techniques as well. Martial skill was an important component of ancient culture. The exchange of weapons and related martial arts is likewise an important part of ethnic and Sino-foreign cultural exchange, yet unfortunately academic circles have long neglected it. The Mixi Sabre is a curved sabre, mainly a cavalry weapon. Its crescent shape was meant to better suit mounted slashing and thrusting. This kind of sabre once spread throughout West Asia and Central Asia, and later after the rise of the Ottoman Empire, it became a powerful weapon in Turkish hands. Regardless of what kind of weapon it is, it is always accompanied by a corresponding method of use, and without appropriate requisite martial skill, the weapon’s effectiveness cannot be realized, and may even produce the opposite result. This is common sense.

The presence of the Mixi Sabre in the Ming military indicates that its usage techniques were also transmitted into China and this is a fascinating cultural phenomenon. Until now we only knew that Japanese swords and their methods were introduced into the Ming dynasty and had great influence. (25) Now there is additionally the Mixi Sabre and its sabre techniques. This is a discovery rich in cultural implications, and a captivating topic. Although in existing Ming martial arts texts we have not yet found records of Mixi Sabre techniques, I am convinced that in the military of the Yuan and Ming, and even in the early Qing martial traditions, it once held a place and its lineage was likely connected with the Hui people who valued martial skill.

Written by - Prof. Ma Mingda - Originally published in Studies in Maritime Exchange History Issue One, 2000; revised in 2006.

Translated by Byron Jacobs

Notes

1. Zhang Xian, Yusi Ji Vol. 4. “Mixi” is written as “Anxi” in the Congshu Jicheng edition, but both the Wenyuan Pavilion Siku Quanshu facsimile and the Yuyatang Congshu (First Compilation, Second Collection) print read “Mixi.” The Congshu Jicheng version appears to be a printing error.

2. Du Fu, Collected Poems of Du Gongbu Vol. 7, “Song of the Great-Food Sabre for the Jingnan Marshal Zhao Gong,” Zhonghua Book Company facsimile Song-style edition, 1957, Vol. 1 p. 292.

3. Qing Supplement to Comprehensive Study of Civilization Vol. 134, “Weapons Section · Military Equipment,” Zhejiang Ancient Books Press 2000 facsimile of the Commercial Press Wanyou Wenku edition, p. 3994.

4. Ming He Liangchen, Zhen Ji Vol. 2, “Skills and Applications,” Congshu Jicheng edition.

5. Yuan Liu Yu, Record of the Western Embassy: “To the west lies the country of Miqi’er, exceedingly wealthy, with native gold; at night, when light is seen, it is marked with ashes; the next morning, upon digging, pieces as large as dates may be found.” The same text also writes it as “Mixi’er.” See Wang Yun, Collected Writings of Master Qiujian Vol. 94, Yutang Jiahua Vol. 2, Sibu Congkan edition, Vol. 4 p. 895. In Han Rulin’s History of the Yuan chap. 10, sect. 2, p. 432, note 1 reads: “The Yuan called Egypt Mixi’er. From Arabic Misr, abbreviated from Hebrew Mizrdim.”

6. See Dosson’s Mongol History Vol. 4 chap. 7; Han Rulin History of the Yuan chap. 10 sect. 2.

7. Yuan History Vol. 43 “Annals of Emperor Shun VI,” Zhonghua Book Company punctuated edition, Vol. 3, p. 911.

8. Yuan Zhou Mi, Yunyan Guoyan Lu lower scroll, Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House 1982 Painting Series edition, p. 376.

9. Yuan History Vol. 122 “Biography of Temaichi, with Appendix Biography of Hudu Tiemulu,” Zhonghua Book Company edition 1976, Vol. 10 p. 3003.

10. Zhou Mi Guixin Miscellaneous Notes, continuation Vol. 1, “Western Region Jade Mountain,” Zhonghua Book Company punctuated edition 1988, p. 120.

11. Yuan Huang Jie Bianshan Xiaoyin Yinlu Vol. 2, Taiwan facsimile Siku Quanshu Wenyuan Pavilion edition.

12. Ming Ma Huan Yingya Shenglan Preface “Travel Verse”: “Hulumas near the sea, Dayuan and Mixi trade freely.” Hulumas = Strait of Hormuz; Dayuan appears to be a mistaken reference to Great-Food (Arab lands).

13. See Wang Yude et al., Classified Compilation of Ming Veritable Records · Foreign Relations Volume, p. 1088 “Egypt,” Wuhan Publishing House 1991.

14. History of Ming Vol. 332 “Western Regions IV,” Zhonghua Book Co. punctuated edition, Vol. 28 p. 8619.

The Draft of the Board of Rites Gazetteer Vol. 91 contains “Regulation for Gifts to Mishi (Egyptian) Envoys,” identical to History of Ming but recording the tribute year as Zhengtong 5. The Sultan Ashirafu is written there as “Arslan Khan.”

15. Wusili/Wusili—referring to Egypt under Arab rule, transliteration of Misr. See Sun Yutang, “Sino-African Contact in the Sui-Tang Period,” in Collected Academic Papers of Sun Yutang, Zhonghua Book Company 1995 p. 445.

16. History of Ming Vol. 332 “Western Regions IV,” p. 8598.

17. Yongle Encyclopedia Vol. 3526, Zhonghua Book Co. 1986 facsimile deluxe edition, Vol. 2 p. 2020.

18. Yongle Encyclopedia Vol. 22182, Vol. 8 p. 7867.

19. See Li Hongbin “Analysis of Fine Steel and Bronze Items in the Otani Manuscripts,” in Wenshi Vol. 34.

20. Zhou Wei Sketch History of Chinese Weapons Chap. 3 “Iron Weapons,” Sect. 6, Sanlian Bookstore 1957 p. 259.

21–22. History of Ming · Biography of Han Yong, cited above pp. 4733–4734.

23. Ming Gu Yingtai Historical Events of the Ming Vol. 39 “Pacification of Teng Gorge Rebels.”

24. Ming Han Yong Xiangmin Ji Vol. 8, Taiwan facsimile Siku Quanshu Wenyuan Pavilion edition.

25. See the author’s work “Study of Historical Sword & Sabre Exchange among China, Japan and Korea,” in Collected Essays on the Sword, Vol. 4, Lanzhou University Press, March 2000.